Kowloon Walled City Photography Exhibition

Though decades have passed since its concrete walls stood tall and proud, Kowloon Walled City still evokes strong waves of nostalgia - even for those born well after it came down. Colloquially known as the City of Darkness, its post WWII identity as a self-governing de jure enclave attracted many refugees fleeing the Chinese Civil War. At its peak, the misshapen complex touched the sky in uneven batches of ten to seventeen storey-high blocks and housed more than 33,000 residents. The Walled City covered all of its residents’ needs, from corner shops to dentists, mahjong parlours to restaurants - in only 26,000 square metres.

Three decades after its demolition, the Blue Lotus Gallery invites viewers to experience the “Voices of the Walls” as they step into the past to explore what was and what could have been.

The Walled City’s staggering density didn’t crop up overnight. Original buildings were residential complexes constructed on the principles of squatters’ rights. Humble two to three storey structures were hastily laid out in the 1960s as more people flooded the lawless enclave. “Practical chaos” comes to mind. With no governmental or architectural oversight, the interior was a visual barrage of bare wires, too-narrow passageways, improper ventilation, and a handful of standpipes that supplied all of the city’s water.

Local photographer Keeping Lee recalled all this fondly as he remembered the day he ventured inside. It was 1985, and the Walled City was already the stuff of legends.

Curiosity was Lee’s compass, and he wasn’t the only one. On that fateful day, he ran into another photographer - a Canadian name Greg Girard wanting a local translator to help him interview Walled City residents. Lee smiled at the memory. “It was purely by chance,” he asserted. “But for sure, there was a reason we met [that day].”

While Lee was more agile with a handheld camera, Girard’s setups took time as the photographer needed to set up a flash system that would accommodate the Walled City’s harsh flourescent lights.

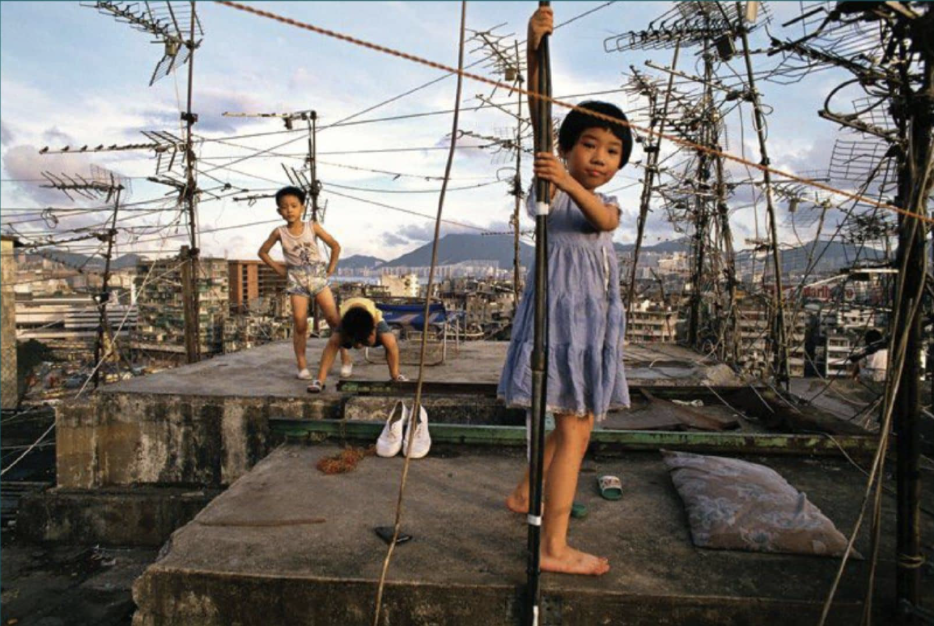

As we poured over each of Lee’s photos on display, I was particularly struck by a sea of antennae. Shot in black and white, these spindles seemed to sprout from the bare concrete rooftops. When I asked how he found his way to the top, Lee shrugged and said it took some time. Initially, he had asked several people for directions, but in the end, he followed some roof-bound children on the hunt for fresh air. As for why he chose to shoot in black and white, Lee simply said, “It just felt right.”

Built from whatever materials were available, the Walled City increasingly resembled a disjointed Lego house - densely packed, lacking any design coherence, but all fitting together nonetheless. It was a particularly stunning site in the afternoon glow. That’s what photographer Ian Lambot wanted to capture.

“As much an engineer as an artist”, Lambot initially trained as an architect. In 1979 he moved to Hong Kong, settling in for 18 years before moving to the UK.

While in Hong Kong, Lambot ran an architectural model-making studio and worked on early-stage development of the Hong Kong Bank project with Foster and Partners. His transition into photography grew naturally from his appreciation for architecture and design, as he wanted to capture the unique characteristics of local constructions. But this would change.

“More time passed”, Lambot explained, “And I realised that the real story is community and people.” Like Lee and Girard, Lambot was fascinated by the self-built city. “It was like the rest of Hong Kong, but squeezed together.”

Clear access was only available on the northern and western sides of the compound, and the southern side was caved in. The afternoon sun illuminated the western face. Wanting to capture the late afternoon glow, he spent an hour preparing his shot. Lambot grinned, recalling it was “a different way of photography”.

He came back to the Walled City time and time again over the next three years. Lambot tried to ask the postman - who could navigate the city with his eyes closed - for help, but the post waits for no one. So, the photographer had to find his own way around. When asked about the assumed dangers that the Walled City presented to outsiders, Lambot shook his head. After the demolition announcement and the start of government surveys, the triads moved out. “[The residents] didn’t want outsiders, but it was not dangerous at all.”

Photographs are a window to the past, and AI is a time machine. “AI allows us to merge surrealism with realism,” AI artist Bianca Tse exclaimed. As an art director for an ad agency, Tse said she “felt I needed to conquer AI for my career. And for that, I needed to practice. So, I picked a topic I was passionate about and inspired by.”

Unlike the other exhibitionists, Tse never set foot in the Walled City. She needed original prints to draw from historical memories and create her renditions of Walled City life. Reaching out to Girard, Tse explained her vision and asked if he could help. He agreed, giving her a task.

There was one specific image he didn’t manage to capture while the Walled City was up, and he wanted to see if Tse could bring the image to life. “It was a Cathay Pacific stewardess, and she was in a rush. He didn’t have time to set up the photo.” The contradictory nature of the image that stuck with him. It was rare to see a symbol of governance inside the Walled City.

“For me, the Walled City represents a lot of personal memories,” Tse said. “I lived in temporary housing with my family, so they were similar conditions.” Since the demolition of the Walled City, an increasing amount of older housing units in Hong Kong have been torn down, their structures deemed inadequate according to modern health and safety standards. But destroying these buildings outright means wiping away a unique piece of local culture. Maybe more of us will turn to AI to recapture old memories.

Rising from the ground out of sheer force of will, Kowloon Walled City is proof that community is the de facto nature of a functioning society, and chaos is a matter of definition. While the structure was not intentionally designed and posed countless dangers, it functioned as a self-governed city for almost one hundred years, from its initial settlement around 1898 to the end of its year-long demolition in 1994. Like Kai Tak Airport before it, we wave goodbye to the past and continue to explore this unique piece of Hong Kong history through vintage photographs and new artwork.

Originally published in CULTURE Magazine Issue 239 (November-December 2024)